July 25, Lvov, Ukraine

It's 9:30 pm of a day off here in lvly

Lvov (aka Lemberg or Leopolis), a gem of a city here on the western edge of Ukraine, nestled at the foot of the Carpathian mountains, the historic capital of the region of

Galicia.

I really like the feel of this city. It is a piece of the Austro-Hungarian empire marooned in Ukraine, full of Catholic churches, cafes and elegant fin-de-siecle architecture. It's a bit like Budapest in its feel, thanks to the century and a half that the Hapsburgs ruled the city. It was actually a Polish city for centuries before that, a major trading centre in Eastern Europe and a major centre of Jewish, Polish, Armenian and even Greek culture. I arrived here yesterday at midday and have spent the past day and a half poking about, sampling the excellent cakes and hot chocolate (more Viennese influence) and looking at the architectural eye candy.

Before I start blogging, I should mention that the right sidebar contains links to the

Google Map showing my route, and the

Google Doc table with all the daily riding statistics, for those of you who want to keep a closer eye on where I've been.

Since I last blogged from Kosice, the monsoon season seems to have arrived here in central Europe, with some rain on each of the past 8 days. Some days it has mostly rained at night, but other days have been pretty soggy on the bike. Here's the skinny on what I've been up to for the past week.

Superb Slovakia

I didn't know what to expect in Slovakia; it was a bit of a mental black hole before this trip. I have to say that, although I was only in Slovakia for 4 nights, I was greatly impressed with the country as a cycling destination, and as a pretty, outdoorsy, historic country, with good, cheap food and good bike shops.

In Kosice I had my front and back hubs tightened and my bottom bracket (the thing that goes through the frame to hold the pedals) replaced. I had been hearing cracking noises from the bike as I pedalled, and I thought that it meant that one of the ball bearings in the bottom bracket had broken. The mechanics replaced the bottom bracket, but told me that in fact the bottom bracket bearings had been fine, although it was the wrong diameter, and that probably because it was too small, it wasn't being held in place properly. As soon as I pedalled off, I realized that I had misdiagnosed the problem. The noises were unchanged, and I realized that it must be the freewheel, the bit of the back axle assembly that allows you to coast downhill without pedalling. This is a more major reconstruction job, involving rebuilding the rear wheel around a new axle, so I want to avoid doing this on the road if I can at all avoid it. I have, however, bought a new axle with a properly functioning freewheel, in case I have to have a new wheel built in the next month somewhere with fewer bike shops and less access to quality bike parts.

I rode out of Kosice a bit groggy, after a huge thunderstorm kept waking me up in the middle of the night. I pedalled north at first to Presov, leaving behind the broad agricultural fields around Kosice and heading towards the foothills of the Carpathians. I then turned west and headed towards the highest part of the entire Carpathian range, the renowned

High Tatras. I was hoping to do some hiking, but as I approached the mountains, I realized this was not going to happen; the peaks were completely covered by black thunderclouds, and the weather forecast was for much more of the same.

I still managed to see some lovely stuff, despite the bad weather. After a bit of a rollercoaster ride against the grain of the landscape, I coasted down from a reasonable climb and was greeted by the sight of an outsized castle dominating the landscape from atop a steep ridge. It was Spis Castle, the biggest castle in Slovakia and one of the largest in all of Europe. It was hard to get a decent picture, as clouds stayed stubbornly directly overhead, but it was impressive to see from different angles as I rode past. It marked the start of the Spis region, devastated by Mongol invasions in 1242 and repopulated by Saxon German settlers invited in by the King of Hungary. Spis is full of little medieval towns with pretty market squares, castles, Gothic churches and lovely housefronts.

I rode through one of the standouts,

Levoca, which has made it onto UNESCO's World Heritage list. The main square was outstanding, with extremely pretty houses everywhere attesting to a prosperous Middle Ages for the town, based on trade. The main square was dominated by a huge Gothic church famous for its 18-metre-high carved wooden altar, supposedly the biggest wooden Gothic altar in the world.

It was carved by Levoca's most famous son, the sculptor

Master Paul. There was scaffolding on the altar when I ventured into the church, but a nearby museum has excellent high-quality replicas of the carvings that you can get up close to and photograph. The church was full of astrophysicists, attending a big conference on exoplanets in the High Tatras. It was funny to run into people from my previous life; in fact, one of the scientists I talked to was at Harvard when I was there (1992-94) and was the advisor for one of my fellow grad students, although I don't think we ever met.

I pushed on, into black, ominous skies, headed for the city of Poprad, but the increased hilliness and impending downpour had me looking for a place to sleep indoors.

I found a little motel and got one of the better deals on rooms of the trip: 15 euros for a luxurious, enormous room with satellite TV and a big breakfast in the morning. I turned in early, replete with sausages, sauerkraut and potatoes, perfect fuel for another day in the saddle. I felt really tired, perhaps from two nights of poor sleep in my tent in the pouring rain.

All day I had noticed that many of the villages I passed through seemed to have a majority

Roma (Gipsy) population. There seem to be a greater percentage of Roma in Slovakia than almost anywhere else in eastern Europe. Many non-Roma Slovaks that I spoke to displayed a pathological hatred for the Roma, and said some truly vile things about them, the sort of things that Nazis said about the Jews. I found it quite disturbing. While it's true that the Roma are in general poorer than other Slovaks, they seem to be doing materially better than the Roma in Romania or the Balkans, with quite a few members of a Roma middle class visible on the streets.

On the other hand, there are a couple of definite favelas on the outskirts of some towns, and some Roma are extremely poor indeed. I remember a story a few years ago in which the mayor of a small town in Slovakia bought plane tickets to Canada for all the Roma inhabitants of his town and told them to claim refugee status when they landed. I get the feeling that a lot of Slovaks would like to do the same thing to their local Roma inhabitants. George Soros, as part of his Open Societies projects, is trying to help the

poor state of public health provision to eastern Europe's Roma communities.

That night there was an apocalyptic thunderstorm that left me happy to be indoors. I got going relatively early and cut a corner to avoid Poprad and head straight to another pretty Saxon Spis town,

Kezmarok. Lovely castle, great town square, and a perfect spot to sip hot chocolate, eat chocolate cake and write postcards. The local river was running very high, and later that day, Slovak TV was carrying stories of flooding in various parts of the country. I was glad that I had decided to abandon thoughts of hiking up the peaks of the High Tatras, which I still hadn't so much as seen through the curtain of rain. I rode off to Stara Lubovna, with the inevitable castle and cathedral and, more to the point, a fantastic restaurant for a vast lunch. Thus fortified, I continued the ride, over increasingly hilly terrain, towards the

UNESCO-listed town of Bardejov.

At one point, looking back, I could just make out, through a break in the rainclouds, the silhouette of the High Tatras; it was the only glimpse I caught of them in two days.

I got to Bardejov having covered 110 fairly tough kilometres, but decided to take advantage of a break in the weather to go see one of Carpathian wooden churches (unusually, this one was Roman Catholic), 10 km uphill out of Bardejov in the village of Hervartov. The setting was perfect, in a copse of trees overlooking the village, and when the sexton showed up with the keys, the interior was amazing, full of Gothic paintings and altars and frescoes.

I coasted back to Bardejov, found a hotel, ate pizza and collapsed into bed, pretty tired after 133 km.

I spent an hour the next day absorbing the wonderful central square of Bardejov. After another night of rain, there was dramatic light, with shafts of light illuminating the pastel facades with black thunderclouds behind.

The museum told the story of another rich Middle Ages trading town, which declined over the centuries as religious war tore apart the fabric of society. The town was burned by Hussites, then converted to Protestantism for a century before converting back to Roman Catholicism.

After bidding a fond farewell to Bardejov, I rode towards the small town of Svidnik. Somewhere along the way, as I properly entered the Carpathians, I crossed an invisible border line between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy, or rather the Austrian-influenced hybrid of the

Uniate church.

The Carpathians are full of pretty little wooden churches, much as I saw in Romania, most of them Uniate and

many of them on UNESCO's list. I spent much of the day visiting these churches, almost all of them Uniate (Greek Catholic; beliefs and rituals are Orthodox, but the church has the Pope as its head, rather than an eastern Patriarch). Some of them have been recently renovated, reducing their atmospheric value, but I really liked Bodruzal,

with ancient wooden walls and roof shingles and a peaceful, small interior.

The road led over the 500-metre-high

Dukla Pass, site of a series of bloody battles between the Red Army and the Wehrmacht in late 1944.

There are German military cemeteries everywhere, and a huge memorial to Soviet, Polish and Slovak soldiers at the summit of the pass. I coasted downhill into Poland and into more rain. I pushed on, through heavy truck traffic, as far as a tiny truck stop motel where I turned in early, shattered again.

The Push Through Poland

This ride through the southwest corner of Poland was a bit of a non-entity in terms of sights and history and culture. I spent the next day riding to the town of Przemysl, along a well-engineered modern road, up and down over low hills, through alternating patches of woods and hayfields. I did 1450 vertical metres that day, but it felt like less, as most of the climbs were very gentle. That day I discovered that I should have put on a new chain while the bike was in the shop in Kosice.

All the rain meant a lot of grit on the chain, and it accelerated the erosion and grinding of the links that meant the chain was getting longer and longer, and starting to skip very badly whenever I was pedalling hard (ie uphill). I decided that Przemysl, my destination for the day, was likely to have a bike shop with new chains and other useful bits of metal.

When I got to Przemysl, a pleasant little Galician town with a lovely Baroque main square, I checked out the bike shops, but found most of them closed. I spent a lazy evening sketching the church facade and eating, and the next morning found me checking the bike shops one more time before leaving town. Several shops were either still closed or didn't have a nine-speed chain, but the last shop I went to had a chain and a friendly mechanic named Marcin who had just come back from five years working in Ireland. I bought the new chain and, in the process of putting it on, realized that the middle chain ring on the front was completely worn out. I tried to replace it, but the new ring I bought didn't fit properly, as Shimano had changed its specifications. The next several hours were spent trying to remedy this problem, and the final solution was to buy a new crank set (pedal arms and three front chain rings) which, due to another change in Shimano specifications, didn't actually fit on my bike. I then took all the chain rings off and put them onto my old pedal arm. It was a brilliant idea by Marcin, but once again Shimano found a way to foil us. The middle chain ring was a few millimetres too small to fit on the old pedal arm, even though they were exactly the same model number, just from different years. Lots of cursing, then an hour and half of hard work with a metal file and I was able to enlarge the inner surface of the chain ring enough to put the whole assembly together again. Marcin's colleague was impressed with my filing: "You are like McGyver!" High praise indeed.

Return to the Ukraine

By now it was 2 in the afternoon, and there was no way I could make it to Lvov that afternoon. I had pizza with Marcin and his colleague, then pedalled for the border where I had a piece of grim deja vu. Once again the Ukrainian border police insisted that I couldn't cross on my bike, and made me get into a minivan. Once again, we waited forever for lazy, corrupt border officials to deign to let us through. It took two and a half hours to finally get through, so I rode only 20 km into the Ukraine before finding a little hotel (the fourth I tried; the first three were booked out for weddings on this July Saturday night) beside a pond where I ate well, but slept poorly as hordes of drunk Ukrainian revellers shouted and pounded on doors late into the night.

My ride into Lvov yesterday was non-descript, other than the appalling road surface. My new chain rode smoothly on my new front chain rings, but my rear gears had also been badly ground down by the old chain, and skipped badly in my most favourite gears. I realized that in Lvov I was going to have to find a new back cassette to fix the problem once and for all.

Once I finally got through construction and awful cobblestone sections of road into central Lvov, I made my way to the rather charming Cosmonaut Hostel, threw my clothes into an actual washing machine (they still look grim, but less revolting than before; bike grease is hard to get out of clothes!) and set off to see this beautiful city.

Today's cafe crawl brought me through several fine Austro-Hungarian cafes, full of sinfully rich cakes and thick hot chocolate, with occasional stops in museums and churches along the way.

Lunch at the Masoch Cafe (yes, named after

that Masoch, he of masochistic fame) was painful only for the length of time it took food to appear on my table. The real pain was to come when I rode through the inevitable afternoon rain to a bike shop to buy a new cassette. I found exactly what I wanted, but when I went to put it on, I found that Dom Cycle, my new least-favourite bike shop in Switzerland, had enormously overtightened the ring that holds the back gear cassette in place on the hub. No amount of pushing, pulling, grunting and swearing would make it budge, so now tomorrow morning will have to be devoted to finding either a much longer and stronger wrench, or else a long metal pipe to put over the end of my wrench to give myself enough torque to undo the un-handiwork of my overpriced and underskilled Swiss bike mechanics.

It's very frustrating to be held up by mechanical problems, but this all could have been avoided if I hadn't made a classic rookie error and not watched my chain for signs of wear. If I had changed my chain 500 or 800 km earlier, none of this other stuff would have been necessary. I thought I had learned my lesson on my year-long 2001 bike trip, when I had to replace my entire drive train in China, but apparently at nearly 43, I am suffering from premature senility. So, much as I may rail against Dom Cycle as the proximate cause of being stuck in Lvov longer than necessary, the ultimate cause is my own negligence and laziness.

I hope to be out of here by midday tomorrow, if not sooner, headed for Poland for another couple of days before riding into Belarus, another new country for me, at the historic town of Brest. From here on, my predominant heading will be north as I head for the Baltic. Appropriately enough, Lvov is right on the continental divide; its river, now buried underground, flows north into the Baltic, while most of the rivers I have encountered this summer have had the Black Sea as their final destination. With only three and a half weeks left in my summer vacation, it's time to start getting serious about making it to Tallinn. I've now rolled over 3500 km from Tbilisi; another 2000 km or so should see me to Tallinn.

Peace and Tailwinds

Graydon

It started as I rode out of Lvov. On the way out of town, as I passed under the train tracks towards Lublin, I saw a moving memorial to the deportation of Jews from Lvov. Lvov had almost 150,000 Jewish citizens in 1941; almost all of them were sent to Belzec extermination site, along with hundreds of thousands of Jews living in smaller towns around Lvov (the province of Galicia). The statue, of a robed, prophetic man raising his arms to heaven, stood beside plaques saying that this was the start of a road to death and destruction for the Jews of Galicia. I rode out of town, realizing that my road lay almost parallel to the train tracks which would have carried trainload after trainload of victims to Belzec.

It started as I rode out of Lvov. On the way out of town, as I passed under the train tracks towards Lublin, I saw a moving memorial to the deportation of Jews from Lvov. Lvov had almost 150,000 Jewish citizens in 1941; almost all of them were sent to Belzec extermination site, along with hundreds of thousands of Jews living in smaller towns around Lvov (the province of Galicia). The statue, of a robed, prophetic man raising his arms to heaven, stood beside plaques saying that this was the start of a road to death and destruction for the Jews of Galicia. I rode out of town, realizing that my road lay almost parallel to the train tracks which would have carried trainload after trainload of victims to Belzec.

After crossing the border (for once, it was painless), it was a short 15 kilometres to the tiny town of Belzec, only 85 km from the great metropolis of Lvov. There, just across the train tracks, was the memorial I had come to see. Most Westerners, if asked about the Holocaust, can come up with the names of Auschwitz and Dachau, but far fewer know the name of Belzec. And yet, in some sense, it was Belzec, along with Sobibor and Treblinka, that were the very heart, the epicentre of evil, of Hitler's Holocaust. At the Wannsee Conference in early 1942, chaired by Reinhard Heydrich, the decision was made to kill all the Jews in the General Government of Poland (most of the Polish territories captured in 1939). The Jews further east, in the parts of Poland captured by the Soviets in 1939 as well as Soviet Lithuania, Belarus and Poland, were killed in large numbers in 1941, but those in the General Government were still alive, herded into ghettoes and exploited as slave labour. After Heydrich's murder in May, 1942 in Prague, the operation to kill Poland's Jews was named Operation Reinhard in his honour. Belzec was the first of three extermination camps constructed for this purpose, and it operated from late March to December of 1942. In that time, nearly 500,000 Jews were murdered here, and only 2 were known to have escaped. Perhaps it's this grisly efficiency that has kept Belzec out of the public eye; there was nobody left to tell the story.

There's also nothing left to see. Unlike Dachau and Auschwitz, which were captured more or less intact and functioning, Belzec (and its sister facilities at Sobibor and Treblinka) had long since served its hideous purpose. After the last murders in December, 1942, the site was completely dismantled. In 1943 a group of Jewish slave labourers was brought in to dig up the bodies and completely burn them. The ashes were then reburied, the site was planted with trees and the labourers were sent to their deaths at Sobibor. It was as though this site of immense evil, along with the hundreds of thousands of victims, had never existed. To this day, Galicia has almost no Jewish inhabitants; Hitler's mad dream came true, and few of the handful of survivors remained. Galicia, once a vibrant mix of Polish Catholics, Ukrainian Orthodox believers, Jews, Roma, Germans and Armenians, has been simplified by Hitler, and subsequent post-WWII ethnic resettlements, into an almost entirely Ukrainian area. The fact that so few people know today about Belzec only adds to the sense that Hitler's attempts to cover up the crimes have succeeded to a large degree.

After crossing the border (for once, it was painless), it was a short 15 kilometres to the tiny town of Belzec, only 85 km from the great metropolis of Lvov. There, just across the train tracks, was the memorial I had come to see. Most Westerners, if asked about the Holocaust, can come up with the names of Auschwitz and Dachau, but far fewer know the name of Belzec. And yet, in some sense, it was Belzec, along with Sobibor and Treblinka, that were the very heart, the epicentre of evil, of Hitler's Holocaust. At the Wannsee Conference in early 1942, chaired by Reinhard Heydrich, the decision was made to kill all the Jews in the General Government of Poland (most of the Polish territories captured in 1939). The Jews further east, in the parts of Poland captured by the Soviets in 1939 as well as Soviet Lithuania, Belarus and Poland, were killed in large numbers in 1941, but those in the General Government were still alive, herded into ghettoes and exploited as slave labour. After Heydrich's murder in May, 1942 in Prague, the operation to kill Poland's Jews was named Operation Reinhard in his honour. Belzec was the first of three extermination camps constructed for this purpose, and it operated from late March to December of 1942. In that time, nearly 500,000 Jews were murdered here, and only 2 were known to have escaped. Perhaps it's this grisly efficiency that has kept Belzec out of the public eye; there was nobody left to tell the story.

There's also nothing left to see. Unlike Dachau and Auschwitz, which were captured more or less intact and functioning, Belzec (and its sister facilities at Sobibor and Treblinka) had long since served its hideous purpose. After the last murders in December, 1942, the site was completely dismantled. In 1943 a group of Jewish slave labourers was brought in to dig up the bodies and completely burn them. The ashes were then reburied, the site was planted with trees and the labourers were sent to their deaths at Sobibor. It was as though this site of immense evil, along with the hundreds of thousands of victims, had never existed. To this day, Galicia has almost no Jewish inhabitants; Hitler's mad dream came true, and few of the handful of survivors remained. Galicia, once a vibrant mix of Polish Catholics, Ukrainian Orthodox believers, Jews, Roma, Germans and Armenians, has been simplified by Hitler, and subsequent post-WWII ethnic resettlements, into an almost entirely Ukrainian area. The fact that so few people know today about Belzec only adds to the sense that Hitler's attempts to cover up the crimes have succeeded to a large degree.

With nothing visible to look at, a huge artificial memorial was established in 2004. A large field of volcanic rock has been created, ringed by tangled steel rebar and the names of cities whose Jewish inhabitants rode the rails to Belzec. A few railway sleepers and rails have been dug up; they were probably used as pyres during the 1943 coverup operation. A passage leads gradually underground through the rocks to a huge stone face inscribed with an inscription from the Book of Job: "Earth, do not cover my blood. Let there be no resting place for my outcry!" in Polish, English and Hebrew. I found it very moving in its minimalism. An underground museum has also been built, very simple and compelling in its exhibits and information. You can easily read all the captions and information panels in under an hour, but it will stay in your memory for life.

I pedalled away towards Zamosc and its Renaissance core, where a wonderful Renaissance synagogue now stands empty; there are no Jewish citizens of Zamosc anymore. I went to bed very pensive, pondering the ghosts of history.

The next day was more of the same. I rode a long day through the gently rolling farmland of eastern Poland, through the city of Chelm, towards the point where the modern borders of Belarus, Poland and Ukraine meet. All the way, there was a train line somewhere close to the road, and again it was a silent witness to the horrors of the 1940s. I passed through Izbica, which was mentioned in the Belzec museum as a concentration camp that served as a feeder to the death factories of Sobibor and Belzec. This time no memorial plaque or sign was in evidence. I pedalled north into a pretty area of flat forest and small lakes, much beloved of fishermen and local Polish tourists on bicycles. The Dutch province of Gelderland (where my father hails from, originally) has helped the Polish government set up a network of bike trails to explore this area.

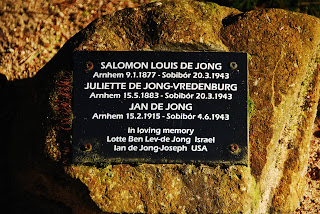

In the centre of the forest, straddling (naturally) a railway line, lies Sobibor death camp. This time, as I had already ridden 115 km, it was too late to get into the museum, but the open-air site was still open. Again, there are no physical remains of the facility; the Nazis obliterated it in 1943 as well. The memorials here are much simpler, but in some ways more moving and more disturbing. The trees planted in 1943 have grown up into a magnificent forest. Although I generally love forests, the evil done in this place lends a malevolent air to the trees. Along one path in the forest, a series of memorial stones have been laid to commemorate individuals known to have died in Sobibor.

With nothing visible to look at, a huge artificial memorial was established in 2004. A large field of volcanic rock has been created, ringed by tangled steel rebar and the names of cities whose Jewish inhabitants rode the rails to Belzec. A few railway sleepers and rails have been dug up; they were probably used as pyres during the 1943 coverup operation. A passage leads gradually underground through the rocks to a huge stone face inscribed with an inscription from the Book of Job: "Earth, do not cover my blood. Let there be no resting place for my outcry!" in Polish, English and Hebrew. I found it very moving in its minimalism. An underground museum has also been built, very simple and compelling in its exhibits and information. You can easily read all the captions and information panels in under an hour, but it will stay in your memory for life.

I pedalled away towards Zamosc and its Renaissance core, where a wonderful Renaissance synagogue now stands empty; there are no Jewish citizens of Zamosc anymore. I went to bed very pensive, pondering the ghosts of history.

The next day was more of the same. I rode a long day through the gently rolling farmland of eastern Poland, through the city of Chelm, towards the point where the modern borders of Belarus, Poland and Ukraine meet. All the way, there was a train line somewhere close to the road, and again it was a silent witness to the horrors of the 1940s. I passed through Izbica, which was mentioned in the Belzec museum as a concentration camp that served as a feeder to the death factories of Sobibor and Belzec. This time no memorial plaque or sign was in evidence. I pedalled north into a pretty area of flat forest and small lakes, much beloved of fishermen and local Polish tourists on bicycles. The Dutch province of Gelderland (where my father hails from, originally) has helped the Polish government set up a network of bike trails to explore this area.

In the centre of the forest, straddling (naturally) a railway line, lies Sobibor death camp. This time, as I had already ridden 115 km, it was too late to get into the museum, but the open-air site was still open. Again, there are no physical remains of the facility; the Nazis obliterated it in 1943 as well. The memorials here are much simpler, but in some ways more moving and more disturbing. The trees planted in 1943 have grown up into a magnificent forest. Although I generally love forests, the evil done in this place lends a malevolent air to the trees. Along one path in the forest, a series of memorial stones have been laid to commemorate individuals known to have died in Sobibor.

Although the vast majority of victims were Polish Jews, there were also some victims brought in from the Netherlands, France and Germany. I found it strange, and somehow disturbing, that the memorial stones were almost all for the Dutch victims, often laid by the descendants of the deceased. Some came from Arnhem, close to where my father grew up. Others had the same first name as my father, Gerrit. These coincidences, by creating a feeling of a linkI wondered whether it was partly because so many Dutch Jews managed to survive the war to remember their dead relatives; perhaps there were so few stones for Polish victims because so few of them had any surviving descendants to come lay stones for them. Or perhaps the post-WWII historical narrative of the Soviet bloc, in which Soviet, and especially Russian, victims of the Nazis were paramount, left little time or inclination to consider the Jewish victims of the Nazis. I don't know, but something about it left me feeling uneasy.

Although the vast majority of victims were Polish Jews, there were also some victims brought in from the Netherlands, France and Germany. I found it strange, and somehow disturbing, that the memorial stones were almost all for the Dutch victims, often laid by the descendants of the deceased. Some came from Arnhem, close to where my father grew up. Others had the same first name as my father, Gerrit. These coincidences, by creating a feeling of a linkI wondered whether it was partly because so many Dutch Jews managed to survive the war to remember their dead relatives; perhaps there were so few stones for Polish victims because so few of them had any surviving descendants to come lay stones for them. Or perhaps the post-WWII historical narrative of the Soviet bloc, in which Soviet, and especially Russian, victims of the Nazis were paramount, left little time or inclination to consider the Jewish victims of the Nazis. I don't know, but something about it left me feeling uneasy.

As I took photographs of the overgrown, unused railway siding that once led to the camp, a busload of young Israelis, some wrapped in the Israeli flag, came out of the site singing. They seemed to be on a Holocaust memorial tour, and it must have been even more emotional for them than for me to see this site of mass death, in which an estimated 250,000 people were killed. Sobibor is also little known in the West, again partly perhaps it was so deadly efficient; only about 50 people are known to have survived, most of whom escaped in the prisoner revolt in October 1943 that damaged the facility and led to it being closed.

By pure coincidence, a few days earlier I had stayed in a hotel with satellite TV and had watched a History Channel documentary about Simon Wiesenthal. One of his most notable successes in tracking down war criminals was his location of the commander of Sobibor (and later Treblinka), Franz Stangl, in Sao Paolo in 1967. Stangl was arrested, extradited to West Germany and tried for war crimes. He was sentenced to life in prison, which amounted to six months, as he died of a heart attack in 1970. Much of what we know about Sobibor came to light during this trial.

It was a shock, after all this grim recollection of death and destruction, to ride 10 kilometres through the forbidding forest and emerge at a lake south of Wlodawa (Okuninka) where thousands of people were enjoying a summer afternoon at the lake. Restaurants, fun fairs, bars and shops were packed. Life moves on, even at the site of profound tragedy.

The ride through Belarus, still along the rail lines of pre-WWII Poland, had fewer overt reminders of the Holocaust, although plenty of WWII. Belarus bore the brunt of fighting on the Eastern Front, with around a third of its population dying between 1941 and 1944. There are memorials everywhere to the Red Army, still faithfully tended with fresh wreaths, and memorials to the partisans who fought the Germans from the forests. However, the Jews of modern-day western Belarus (which was part of Poland occupied by the Russians) suffered horribly in the war years, most of them summarily executed in 1941, immediately after the German invasion, shot in forests and buried in mass graves by the SS and locally recruited death squads.

Arriving here in Vilnius, dubbed the Jerusalem of the North by Napoleon, there are more remembrances of the Holocaust. Vilnius had 140,000 Jewish citizens in 1940, and there were some 200,000 in the country as a whole. Fewer than 10,000 would survive the war. I went to the Lithuanian national holocaust memorial museum, a moving tribute to the destruction of an entire community and way of life. On my way out of town tomorrow, riding toward the coast, I will pass Pareniai, where so many Vilnius Jews were executed in pits dug outside the city.

This section of the bike trip has taught me a lot I didn't know about what happened in WWII in eastern Europe, something that is often passed over lightly in our Western history books. It has also left me saddened, thinking of how often this sort of wholesale destruction of a people has been attempted over the centuries (the North American Indians, the Australian Aborigines, Rwanda's Tutsis, the Armenians of eastern Anatolia, entire city-states in Central Asia during the Mongol onslaught, to name but a few cases). I wonder whether, as Earth's population continues to skyrocket and as more and more people aspire to a Western standard of living, putting increasing strains on land, water, food, forests, oceans, whether we will see a resurgence of this sort of lebensraum idea and killing and mass deportation to achieve it. Today war criminals get sent to the Hague; perhaps in 50 years they will be given medals by their countries instead.

Postscript, Kaunas, August 7

As I took photographs of the overgrown, unused railway siding that once led to the camp, a busload of young Israelis, some wrapped in the Israeli flag, came out of the site singing. They seemed to be on a Holocaust memorial tour, and it must have been even more emotional for them than for me to see this site of mass death, in which an estimated 250,000 people were killed. Sobibor is also little known in the West, again partly perhaps it was so deadly efficient; only about 50 people are known to have survived, most of whom escaped in the prisoner revolt in October 1943 that damaged the facility and led to it being closed.

By pure coincidence, a few days earlier I had stayed in a hotel with satellite TV and had watched a History Channel documentary about Simon Wiesenthal. One of his most notable successes in tracking down war criminals was his location of the commander of Sobibor (and later Treblinka), Franz Stangl, in Sao Paolo in 1967. Stangl was arrested, extradited to West Germany and tried for war crimes. He was sentenced to life in prison, which amounted to six months, as he died of a heart attack in 1970. Much of what we know about Sobibor came to light during this trial.

It was a shock, after all this grim recollection of death and destruction, to ride 10 kilometres through the forbidding forest and emerge at a lake south of Wlodawa (Okuninka) where thousands of people were enjoying a summer afternoon at the lake. Restaurants, fun fairs, bars and shops were packed. Life moves on, even at the site of profound tragedy.

The ride through Belarus, still along the rail lines of pre-WWII Poland, had fewer overt reminders of the Holocaust, although plenty of WWII. Belarus bore the brunt of fighting on the Eastern Front, with around a third of its population dying between 1941 and 1944. There are memorials everywhere to the Red Army, still faithfully tended with fresh wreaths, and memorials to the partisans who fought the Germans from the forests. However, the Jews of modern-day western Belarus (which was part of Poland occupied by the Russians) suffered horribly in the war years, most of them summarily executed in 1941, immediately after the German invasion, shot in forests and buried in mass graves by the SS and locally recruited death squads.

Arriving here in Vilnius, dubbed the Jerusalem of the North by Napoleon, there are more remembrances of the Holocaust. Vilnius had 140,000 Jewish citizens in 1940, and there were some 200,000 in the country as a whole. Fewer than 10,000 would survive the war. I went to the Lithuanian national holocaust memorial museum, a moving tribute to the destruction of an entire community and way of life. On my way out of town tomorrow, riding toward the coast, I will pass Pareniai, where so many Vilnius Jews were executed in pits dug outside the city.

This section of the bike trip has taught me a lot I didn't know about what happened in WWII in eastern Europe, something that is often passed over lightly in our Western history books. It has also left me saddened, thinking of how often this sort of wholesale destruction of a people has been attempted over the centuries (the North American Indians, the Australian Aborigines, Rwanda's Tutsis, the Armenians of eastern Anatolia, entire city-states in Central Asia during the Mongol onslaught, to name but a few cases). I wonder whether, as Earth's population continues to skyrocket and as more and more people aspire to a Western standard of living, putting increasing strains on land, water, food, forests, oceans, whether we will see a resurgence of this sort of lebensraum idea and killing and mass deportation to achieve it. Today war criminals get sent to the Hague; perhaps in 50 years they will be given medals by their countries instead.

Postscript, Kaunas, August 7

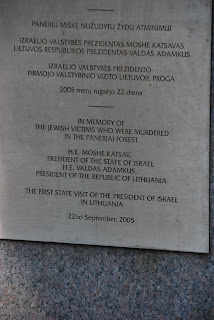

On my way out of Vilnius two days ago, I stopped in the forest of Paneriai, the principal site of executions of Lithuanian Jews from 1941 to 1944. As in much of the territory conquered by the Germans in 1941, from the very first days of the invasion, there were mass killings of local Jewish citizens. At first, the Germans stirred up local nationalists, angered by 2 years of Soviet oppression, by equating Jews to the hated Communists, and there were a number of unorganized killings by Lithuanian militias. Quite soon, however, the Germans organized matters and had the Lithuanian police battalions carry out their dirty work. Nearly 100,000 people were murdered in Paneriai, and most of them were subsequently dug up, burned and then the ashes reburied. I had the forest to myself in the early morning, and walking around the various Soviet and post-Soviet memorials was very moving.

On my way out of Vilnius two days ago, I stopped in the forest of Paneriai, the principal site of executions of Lithuanian Jews from 1941 to 1944. As in much of the territory conquered by the Germans in 1941, from the very first days of the invasion, there were mass killings of local Jewish citizens. At first, the Germans stirred up local nationalists, angered by 2 years of Soviet oppression, by equating Jews to the hated Communists, and there were a number of unorganized killings by Lithuanian militias. Quite soon, however, the Germans organized matters and had the Lithuanian police battalions carry out their dirty work. Nearly 100,000 people were murdered in Paneriai, and most of them were subsequently dug up, burned and then the ashes reburied. I had the forest to myself in the early morning, and walking around the various Soviet and post-Soviet memorials was very moving.