Our time in Rwanda was brief, even for a country as small as this one. We were in a bit of a hurry to get to Uganda before Christmas, and we knew that many of the sights to be seen in Rwanda could be seen in Uganda more easily and more inexpensively, so we ended up skimming through the country a bit more rapidly than would perhaps be advisable.

|

The endless green hills of Rwanda

|

We crossed into Rwanda from Burundi on December 13th. The border was chaotic on the Burundian side, with dozens of would-be fixers, currency exchange guys and carwashers running around, shouting and generally being obnoxious. We exchanged our leftover Burundian francs quickly and then drove to the relative calm of the customs enclosure. It took next to no time to get ourselves and Stanley stamped out of Burundi, but entering Rwanda was a much more leisurely affair, with the customs officials declaring that they wanted to see everything that was packed inside Stanley. When they saw how full the camper was, they compromised on a ten-minute inspection before they got bored. We bought an East African Visa for US$ 100 each, giving us three months in Rwanda, Uganda and Kenya, and it took longer than it might have for the Rwandan border official to fill out the paperwork, find the visa sticker and stamp us in. Luckily there were huge numbers of large fruit bats hanging head-down in the nearby trees, so we had something to look at and photograph during the whole process. We rejected offers to change money at a laughably poor rate and drove into Rwanda.

|

Serious amounts of sugar cane on the move

|

The first few minutes of driving into a new country are always an educational experience as we look for what's new and different from the previous country, and what's the same. Rwanda and Burundi are twin countries in terms of having similar land areas, populations and ethnic makeup (84% Hutu, 15% Tutsi, 1% Twa), and also in terms of both having had unimaginable violence and genocide inflicted on their populations. Rwanda was the first of the two to lapse into genocide, with thousands of Tutsis massacred by Hutu revolutionary mobs between 1959 and independence in 1962. Hundreds of thousands of Tutsi refugees fled, mostly to Uganda, the previously downtrodden Hutus took control of the reins of government, and the seeds were sown for the even larger genocide of 1994. The 1994 genocide colours everything in today's Rwanda, with the RPF government's legitimacy stemming from its role as the group that brought the killings to an end in July, 1994 after 100 days of slaughter that left nearly 1 million Tutsis and moderate Hutus dead. Of course it's not quite as simple as that; a compelling book, Do Not Disturb, by the journalist Michela Wrong, which both Terri and I had read just before our visit to the country shows how the RPF itself also indulged in large-scale atrocities after taking control of the country, and how Paul Kagame's government has built up a police state with a Putin-like propensity for imprisoning or killing those it deems disloyal to the state, both within Rwanda and, frequently, abroad.

|

Huye's main street

|

None of this was visible to us as we drove slowly north towards Huye, the university town formerly known as Butare. What was visible was the number of bicycles on the road, despite the precipitous grade of the smooth asphalt. As was the case in Burundi, bicycles are the transport vehicle of choice for people in rural Rwanda, and it was impressive to see 100 kilograms or more of bananas being pushed up the hill by two wiry men bathed in sweat. There were more people on bicycles and fewer on foot than in Burundi, and as we approached the hilltop college town, there were far more motorcycles and cars on the road than we had seen anywhere in Burundi. Huye itself was a complete surprise, with neatly laid-out commercial blocks, bike lanes and sidewalks and a suburb of big, prosperous-looking suburban villas. There were banks and ATMs everywhere, the shops were bustling, and there was clearly a large and thriving middle class to be seen in the town. It looked as prosperous as Victoria Falls in Zimbabe or Lusaka, Zambia, and a world away from the grinding, obvious poverty just to the south in Burundi. The roads and back streets were smoothly paved, and we drove, mouths agape, to the Heroes Motel to check in. It was a pleasant suburban garden dotted with neat motel modules, and it looked like a good spot to base ourselves for a couple of nights, especially at a price of US$12 per night for the two of us.

We wandered around, a bit dazed by the variety of goods for sale. We availed ourselves of the ATMs and headed off to dinner at a Chinese restaurant. The food was plentiful, excellent and not terribly expensive, although pricier than it had been in Burundi. The owner was a Chinese businessman, while the clientele was a mix of tourists, NGO workers and middle-class hipster Rwandans We ate ourselves into a stupor, then wandered home a few blocks to our motel.

|

The view over the fence of the RNU genocide memorial, Huye

|

We spent the next morning poking around Huye, which is a pleasant town. Unlike in Burundi, we weren't particularly objects of curiosity and gaping, and the bike paths, broad streets and orderly traffic made cycling around on our folding bikes a pleasure. We bought SIM cards for our phones, although there was some sort of mass outage of the cellular data system so we couldn't access the internet. We rode to a coffee shop in search of wi-fi. The wi-fi turned out not to exist, but the coffee was (according to Terri) very tasty, and it was a pleasant place to sit, eat and read for a while. On the way out, we bought some Rwandan coffee for Terri and then rolled downhill towards the National University of Rwanda.

|

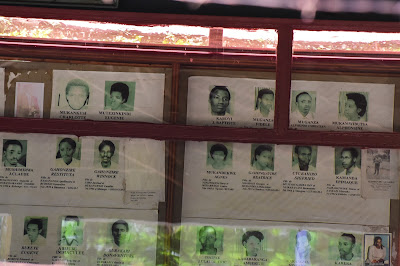

| Some of the staff at RNU who were hacked to death in 1994 |

I wanted to visit the campus' genocide memorial; the campus had been the site of terrible atrocities as Tutsi students and staff as well as intellectual Hutus were hacked to death by Hutu death squads. However, the campus security staff barred us from entering the campus, and were not at all helpful in letting us know how we could get permission. We ended up walking along the main road and peering over the fence at the memorial. It was the first time, although not the last, that the Rwandan authorities' desire to control society and individuals would manifest itself.

|

| A stunning sunbird in Huye |

As a plan B, we went for a short walk in a forest reserve opposite the university campus. Although Rwanda is far less litter-strewn than countries like Zambia and Tanzania, this was not the case in this glade, which was clearly used to dump rubbish. As we climbed back up towards the campus, we spotted playful and mischievous vervet monkeys who were fun to watch as they chased each other around the ornamental shrubbery, climbed up the sides of the student dorms and then ran across the busy main road. Vervets, when they're not actively pillaging your campsite, are actually fascinating to watch in action.

We passed a lazy afternoon back at the motel, reading and catching up on sorting photos (a never-ending task!). The motel grounds were full of colourful sunbirds, and we spent a while seeking them out as they flitted restlessly in search of flower nectar.

The following morning we set off for Kigali. I was pleased to find that my Visa card worked to pay for diesel, while the Vodaphone office was able (finally) to get our SIM cards functioning. The drive to Kigali was relatively easy, with less up-and-down undulation than you might expect, given the relentless verticality of the landscape. As in Burundi, more or less every square centimetre was under cultivation, but the houses we saw were several steps up in terms of livability. The highway was perfectly smooth tarmac, and for the first half of the journey had not too much traffic. That changed at a junction with a road leading west to Lake Kivu, and we spent the rest of the trip trying to pass a long succession of slow-moving heavy goods vehicles, many of which looked as though they were heading to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

|

The role of France in the runup to the genocide

|

|

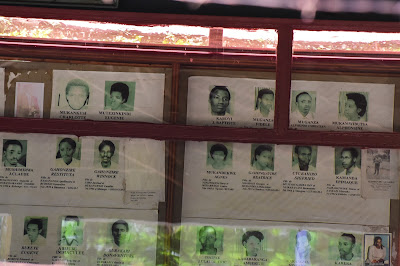

Photos of genocide victims, Kigali

|

Once in the city, we made a bee-line for the legendary German Butchery, keen to restock our freezer with delicious meats and cheeses. The Butchery is an NGO project designed to develop markets for Rwandan produce and meat, and it was fabulous. The meat was high quality and very reasonably priced, and we ended up spending nearly US$100 buying so much food that we could barely get our trusty Engel freezer closed. We then settled in for a delicious lunch at their restaurant which was populated almost entirely by Western expats working at local NGOs and embassies.Replete with pizza and beef stroganoff, we then drove to the one obligatory stop in Kigali, the Kigali Genocide Memorial. Terri had visited years before and had found it so emotionally wrenching that she didn't want to repeat the experience. It took twenty minutes or more to get through the security checkpoint for cars at the entrance to the parking lot; security is a major concern for the RPF government. I spent an hour and a half wandering through the exhibits and the memorial plaques.

It's a very professionally-presented memorial, but also completely devastating in its unflinching portrayal of the decades leading up to 1994, the progressive demonization of the Tutsis as "cockroaches" that needed to be exterminated, and the hundred days of blood-stained frenzy that started when the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi were assassinated, ironically while returning by air from a peace conference in Tanzania. The identity of who fired the surface-to-air missile that brought down the airplane carrying the two presidents is still a matter of sharp controversy, but most third-party observers now seem to agree that it was fired by the rebel forces of the Rwandan People's Front.

|

| One single child victim |

The RPF was founded in Uganda among descendants of the Tutsis who fled the 1959 genocide, and many of its members had already fought for years in the Ugandan civil war, helping to bring Yoweri Museveni to power in 1986. After playing a key role in rebuilding Uganda after the bloodshed and chaos of Milton Obote's second administration, many of these hardened guerrilla fighters turned their eyes westward to their ancestral homeland and decided to try to overthrow the Hutu-led government in Kigali. The Rwandan president, Juvenal Habyarimana, surrounded himself with a coterie of radical Hutu Power extremists who openly advocated the massacre of Tutsis, and whose violent rhetoric became increasingly genocidal as the RPF advanced through northeastern Rwanda. The killing of the president provided the trigger for violence that had been planned with ruthless efficiency for months. Lists of moderate Hutu politicians and civil servants, along with longer lists of Tutsis, had been prepared, and were now used to round up "enemies of the Hutu people". The small UN peacekeeping force, UNAMIR, was tiny and outnumbered, and a notoriously cruel incident early on in which 10 Belgian peacekeepers were captured, tortured and gruesomely murdered made the UN reluctant to risk more peacekeepers by intervening.

I was in graduate school in 1994, and I remember following the events in Rwanda with an appalled fascination. The international community failed utterly to intervene in any meaningful way for over three months, and the first intervention, by the French military, was actually on the side of the genocidaires, trying to prevent the overthrow of a Francophone government by a group of Anglophone rebels. The completely supine response by the UN and by Western governments was indefensible, and motivates the current government (led by those one-time RPF rebels, who ended up driving the genocidaires into exile in July of 1994) to be utterly dismissive of any Western criticism of Rwanda's human rights record or its long list of assassinations on foreign soil.

The larger-scale political dimensions of the genocide were not foremost in my mind as I wandered through the exhibit halls. Instead I was drawn to the individual stories of victims of the massacres: elderly grandparents; parents who died trying to save their children; schoolchildren; prominent political figures; ordinary citizens butchered by their neighbours and even their own in-laws. The faces gazing out at me from the black-and-white photos and their short life stories written down in a few terse sentences tore at my soul and left me feeling nauseated.

One gallery near the end, relating the Rwandan genocide to other grim chapters of 20th century history like the 1915 Armenian genocide, the 1904-07 slaughter of the Herero of Namibia by German colonial forces, the Nazi genocide of the Jews of Europe, the Khmer Rouge's massacre of their own population, universalized what happened in Rwanda as something that could happen anywhere that politicians and military leaders succeed in dehumanizing and demonizing vulnerable populations. It's part of the human condition, albeit a dark and horrifying part that most of us don't want to peer at too deeply. Having visited Nazi death camps in eastern Europe, the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem, the Killing Fields of Cambodia, various museums to Soviet atrocities in the Baltic States, and the Tsitsernakaberd Genocide Memorial in Yerevan, I felt an eerie similarity in what I saw here in Kigali. When you add in governments determined to erase entire cultures (the Tibetans and Uighurs in Communist China, the Chechens and Crimean Tatars in the USSR, the indigenous cultures of North America, the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, the Roma of Eastern Europe), the dreadful universal nature of this sanguinary history comes into a sharper perspective. The behaviour of Russian troops in occupied Ukraine and the shrill bombast of Russian leaders are just another manifestation of this human tendency to other, to demonize and (ultimately) to try to erase troublesome people and cultures out of existence.

|

Names of a few of the million victims, Kigali

|

I emerged, blinking, into the peaceful outdoor memorials and spent a while wandering around, contemplating what had happened around me 28 years previously. It was hard to believe, on this sunny day, surrounded by a bustling city, what horrors had been perpetrated all around me, often by people who still live here. It must be difficult for those who survived the 1994 genocide to realize that many of the people who used machetes and hoes to kill their relatives are still their neighbours today.

We were in a sombre mood as we drove up into the steep hillside neighbourhood of Step Town in search of a place to camp. We had heard that the Step Town Motel was friendly to overlanders, and so it proved. We drove Stanley up the precipitous driveway and parked in the corner of the parking lot, next to a handy outdoor picnic shelter. It was a bit noisy (the motel is a thriving business, and we could hear voices late into the night from the restaurant and from people on their balconies), but clean, friendly and (for Rwanda) fairly inexpensive.

The following day started off with a series of frustrations. We were trying to catch up on our YouTube video editing, and Terri was trying to communicate with Olive Tree Learning Centre about year-end financial matters, but the internet was terrible, one of my hard drives stopped working (a few days after I had dropped it on a concrete floor), my telephone camera died (after the soaking it received while tracking chimps in Burundi), WhatsApp stopped functioning, our previously uploaded Christmas video suddenly went on the fritz....These were all definitely First World problems, but they were collectively annoying.

|

Hotel Mille Collines genocide memorial

|

Eventually we threw up our hands, gave up and walked downtown to see the Hotel de Mille Collines, the five-star hotel that was the setting for the events depicted in the film Hotel Rwanda, where the manager saved the lives of hundreds of people who were sheltering there from the genocidaires. In a sign of how completely the current Rwandan government wants to impose its authoritarian control of history onto the world, Paul Rusesabagina, the hero of the story, the man who preserved the lives of so many people in 1994, was arrested in 2020. He was charged with terrorism for daring to oppose Paul Kagame's government, was convicted in 2021 and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Only a month ago his sentence was suddenly commuted and he returned to the US, where he has been a permanent resident for years. We walked steeply uphill to the central business district, along streets full of motorcycle taxis and large SUVs. The Mille Collines is back to functioning as a luxury business hotel, but there are a couple of monuments in the parking lot attesting to the events of 1994. We wandered around, took a few pictures, admired some striking modern Rwandan sculptures and then, just as we were preparing to leave, the skies turned black and one of the biggest cloudbursts of our entire trip descended from the heavens. We headed back to the lobby and sheltered there for an hour as torrents of water lashed down, then gave up on the idea of exploring Kigali and returned to the Step Town.

|

| Looking out at the Hotel Mille Collines pool |

I picked up my malfunctioning laptop and two equally non-performing hard drives, stuffed them into a knapsack and set off on the pack of a motorcycle taxi for a computer repair shop that we had found online. I was not optimistic; I seem to have an aura that destroys electronic gear. This time, however, I hit the jackpot of luck. The computer repair shop was run by an unassuming middle-aged man from Mumbai named Akbar, and he was a wizard. He got one of my hard drives working immediately, and then took apart my laptop, pulled out a large pencil eraser and set to work rubbing the connections of the computer's RAM. A few minutes of erasing, and suddenly my laptop, which hadn't worked since Livingstone (I had bought a backup in Lusaka which I had been using ever since) was alive again. My other hard drive, the one I had dropped, was judged to be completely dead, but (as Meatloaf once sang) two out of three ain't bad. I reached for my wallet, and Akbar refused payment, saying that it had only taken a few minutes, and hadn't involved any real technical skill. I tried to press some payment on him, and he laughed and refused again. I thanked him profusely and hopped back onto another motorcycle taxi to return to Stanley and Maree.

|

The hills of northern Rwanda

|

|

| The hillsides of the Nile-Congo divide |

The next morning we were planning on getting going early, but fate intervened. After sleeping in unexpectedly late, we were starting to pack up when Terri's beloved MacBook Air laptop suddenly stopped working. After fighting with it for a long time and trying to back up as much data as possible, Terri retraced my steps of the previous day and headed to see Akbar. Akbar produced his usual wizardry, and an hour later Terri was back with a resurrected computer. We finally got going at 12:30 with me at the wheel. I promptly got misdirected on the way out of town by our Maps.me navigator, ending up stuck on a steep sidestreet that ended abruptly. It took Terri ten stressful minutes to get us turned around and heading uphill again. Once we got going, in a sea of heavily laden trucks, we settled into a day of steep, unrelenting climbs and descents. On one of them our radiator started to boil and we took twenty minutes to let poor Stanley cool down. As we climbed, our views became more expansive and we began to catch sight of the big volcanoes of the Virunga Range. We stopped a few times for photos of the green hillsides (full of tea plantations) with the volcanic cones behind, but were constantly badgered by kids begging insistently and loudly, so eventually we gave up on photography and concentrated on driving.